Title Details

Title Details

Title

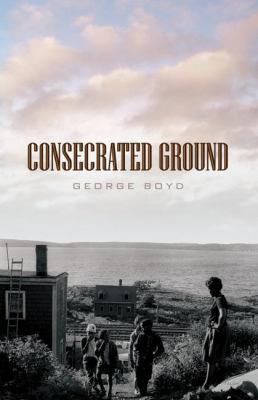

Consecrated ground : a play

Call No

BLK 812.54 B789c

Edition

1st revised printing.

Authors

Subjects

Language

English

Published

Vancouver : Talonbooks, 2011.

Publication Desc

96 p. ;

ISBN

9780889226661

Dimensions

22 cm.

Book

|